Eating meat and dairy is ingrained in cultures

Steak, hamburgers, ice cream — they hardly seem controversial, do they? But interwoven with our food choices is a moral dilemma of global proportions. Producing meat and dairy has catastrophic environmental impacts to the point that moving to a plant-based diet is the most effective measure you can take to reduce your impact on the planet. And yet most people continue eating meat. In fact, demand for meat is on the rise. Now, some of these statements are bound to raise a few eyebrows, so let’s provide a little context.

For starters, what we eat is heavily influenced by cultural norms. Meat and livestock have played a fundamental role in human societies. For thousands of years, people lived in a ‘world of scarcity’ where life revolved around getting enough food to eat. In a ‘world of scarcity’, meat-eating was predominantly a luxury reserved for the wealthiest in society. In other words, hardly anyone ate meat as no one could afford it.

But advances in machinery after the end of the Second World War have led to massive productivity increases that have created a ‘world of abundance’. The result is that food prices have decreased dramatically relative to incomes. And with increasing incomes meat has become affordable to large sections of society, leading to an explosion in global meat consumption. The FAO’s data for 1961 to 2019 shows beef production increased from just under 28 million tonnes to over 68 million tonnes. Pork went from 25 million tonnes to 110 million tonnes; chicken went from 7.5 million tonnes to 118 million tonnes. 50 billion chickens, nearly 1.5 billion pigs and 300 million cows are slaughtered annually to meet the growing demand for meat.

Aside from killing an incomprehensible amount of animals each year, the industrialisation of livestock production has disastrous environmental impacts. The agriculture sector, which includes farming machinery, rearing billions of animals, spraying fertilisers (made from nitrous oxide and phosphorus) and transporting food, leads to over 17 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions each year. 57 percent of the total comes from meat production, 29 percent from growing plant-based foods.

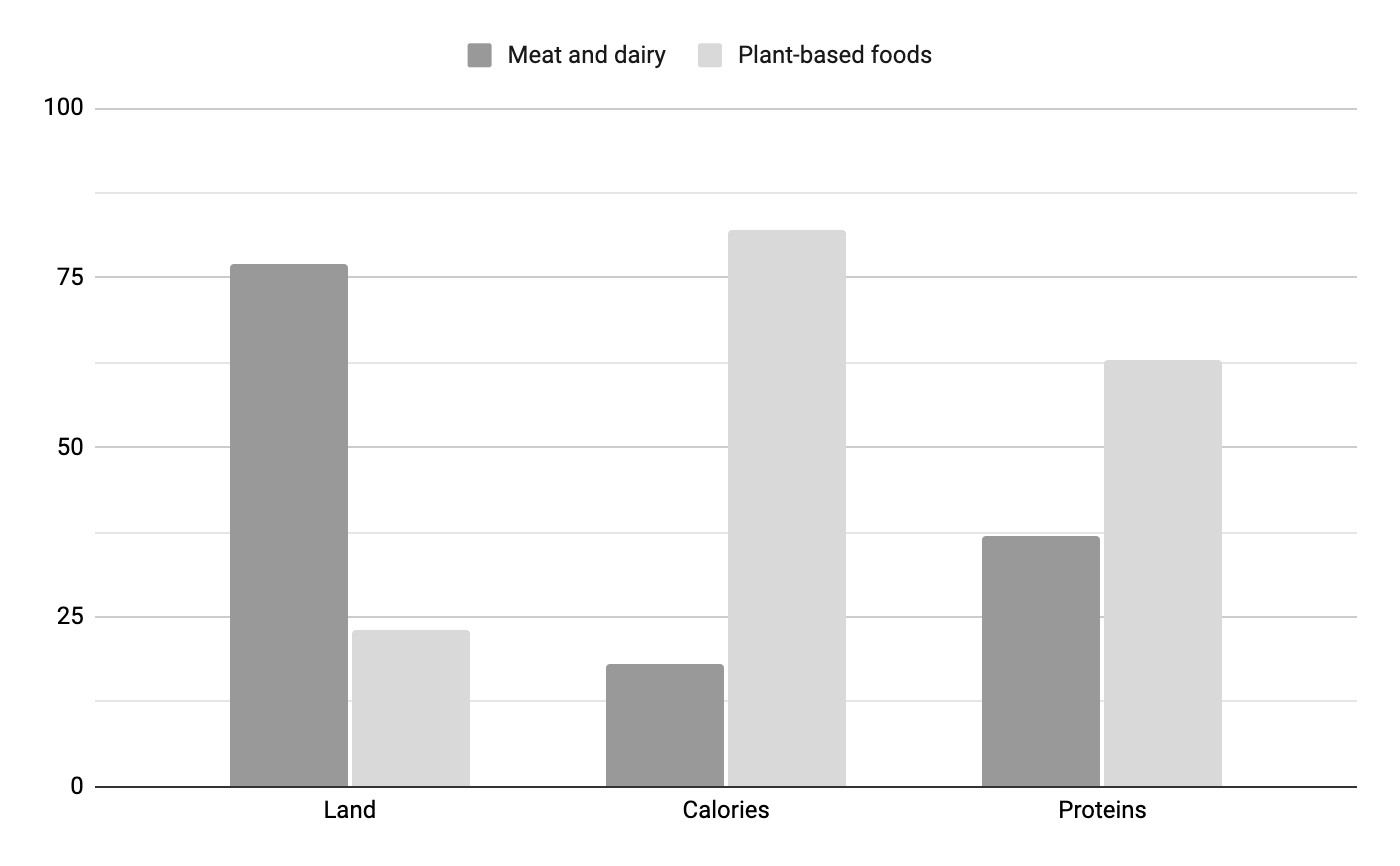

Today half of all the habitable land on Earth is used for agriculture. 77 percent of that land is used to produce meat and dairy; 23 percent is used to grow crops. Meat and dairy account for 18 percent of the calories eaten by humans. The crops provide 82 percent of global calorie needs. An argument justifying a diet rich in meat is that it is a vital source of protein, but only 37 percent of the global protein supply comes from meat and dairy. The other 63 percent comes from plant-based food. What these figures indicate, and what the graph helps to visualise, is that arranging our agricultural sector around meat and dairy production is highly inefficient, particularly when you consider a third of all arable land used to grow crops is allocated to feed livestock.

Rearing cattle is particularly problematic. São Félix do Xingu, an area the size of Ireland, is a municipality of Brazil in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. The area is home to a herd of cattle millions strong. As you can imagine, dense rainforest isn’t conducive to rearing cattle. So not only is the region one of the world’s biggest beef producers, but it’s also known as the deforestation capital of the world.

Forest fires are often started intentionally to clear-cut the rainforest. When trees are burned, they release carbon dioxide they once stored into the atmosphere. That rainforest is then replaced by cows that release methane through flatulence. Not only that but clear-cutting rainforest replaces a thriving habitat with a grassland, destroying biodiversity. As a result of deforestation, the Amazon has been pushed beyond a tipping point. The rainforest now releases more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than it absorbs. We have turned a precious ecosystem into a giant farm and a vital carbon sink into a carbon source, all to meet the demand for beef. What makes this state of affairs even more questionable is a diet rich in red meat is unhealthy, increasing the risk of type two diabetes, cancer and heart disease.

So, eating meat is bad for the environment, it’s bad for the billions of animals processed in this giant industrial machine, and it’s bad for the people who eat it. You would imagine the need to redesign the agricultural sector around a plant-based diet is so overwhelming that it would lead to little resistance. And yet, the sector’s “highly entrenched nature makes it extremely difficult to modify.”

It’s not as simple as wiping the slate clean, hoping everyone forgets they ever ate meat and creating a food system centred on a plant-based diet. After thousands of years of eating meat, it’s become embedded within cultures. And the industrialisation of meat production has created an enormous industry worth an estimated $1.3 trillion. Powerful corporations have vested interests in making sure people continue eating meat. Ultimately, though, while they may entice people with advertising, corporations don’t force meat down people’s throats. Global meat production is estimated to hit 374 million tonnes by 2030 due to increased demand, particularly in China, Brazil and the United States.

This may come as a surprise given the dramatic increase in popularity of plant-based diets in the West. In the UK for example, meat consumption has decreased by 17 percent in the past decade. While sales in the alternative meat market are expected to increase from $4.2 billion in 2020 to $28 billion in 2025. Driving this shift is an increased awareness of the environmental impacts of the meat and dairy industry and the health benefits of a plant-based diet. But it’s also a consequence of higher living standards. In developed nations, meat is so accessible it’s viewed as a basic expectation, not a luxury. And the price of food is so cheap relative to wages that you can pick and choose what you eat, and what you don’t. It’s hard to imagine the 900 million people suffering from hunger are afforded the same luxury. So it’s understandable why meat consumption is increasing in developing nations. A diet comprising meat is aspirational, if you have enough disposable income to afford to buy meat, it’s a symbol of an escape from poverty and a life of newfound wealth and prosperity.

Increasing demand for meat is increasing the intensity of the agricultural sector. Humanity may now be reaching a point where “further agricultural land expansion at a global scale may seriously threaten biodiversity and undermine regulatory capacities of the Earth System (by affecting the climate system and the hydrological cycle).” But that’s precisely what’s set to happen because the FAO estimates food production must increase by at least 60 percent to meet the demands of a population that is predicted to hit nearly ten billion people by 2050.

Cheaper food should benefit everyone. It increases prosperity and is a foundation of thriving societies. Yet social progress driven by technological advancements creates a double-edged sword. Sure, these efficiencies have led to a world of abundance, but it’s not possible for billions of people to eat a diet rich in meat and dairy. The problem, of course, is that what we should do to reduce environmental impacts is very different to what is possible within the context of highly ingrained cultural norms that tend to be very sticky.

Telling someone to stop eating meat because it will reduce emissions won’t work because for starters meat tastes good (I don’t eat meat but it’s hard to deny), secondly, the connection between eating a steak and changes to the climate feels abstract when the climate is changing so slowly as to be unperceivable in people’s daily lives. The result is that the majority will continue to eat what they’ve always eaten because there just isn’t a compelling enough reason to change. The only way we will see change is when there are direct impacts on people’s lifestyles. Mass crop failures brought about by global droughts will lead to grain shortages. Shortages will inevitably see price spikes that will lead to social unrest. That kind of eventuality is likely to come when weather extremes become more ferocious. With the risk of tipping points looming on the horizon that time isn’t as far off as most people realise.