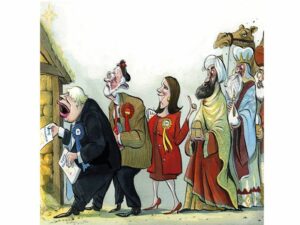

Seemingly worlds apart but with a critical shared characteristic

They’re nothing but gun-loving patriots. They’re intolerant, racist and have a callous disregard for immigrants. So say those on the left about those on the right.

They’re nothing but tree-hugging peacemongers. They’re bad for the economy, always want to raise taxes, and if they get their way we’ll be overrun by immigrants. So say those on the right about those on the left.

Whatever side of the political spectrum you lie on, it’s safe to say views on how society should be governed are polarised. But when you boil political views down, what you’re left with is a common desire to create social prosperity and increase human well-being. These goals are important when you consider we’re in the midst of an ecological crisis (which has inevitably become politicised) that risks debilitating societies and creating untold suffering. The very thing it risks is the prosperity and well-being we all desire.

To avoid that eventuality we need to create sustainable societies where needs are met within the limits set by the natural world. What’s required to achieve that goal is transformation. But what wing of the political spectrum is best placed to take us there?

When we say political spectrum, there are, naturally, a host of misconceptions about what it means to be ‘left’ or ‘right’. But break these terms down and what we’re referring to are different economic systems. That is, different organising principles for how to produce and distribute goods and services to meet human needs. Not to mention any wealth created in the production of those goods and services.

Governments, and how they govern society, are an outcome of economic ideas. This is perhaps the most important thing to recognise about modern societies. We live in economic systems that are managed (or in some cases, not managed) by governments that support economic ideologies.

To think about what political system offers the best chance of creating sustainable societies, we need to think about what each side of the spectrum represents. So what does it mean to be left-wing, right-wing or, the often neglected ‘centre’?

The right-wing — a self-regulating market economy

The idea — in a capitalist market economy the means of production are privately owned.

The foundation of a market economy is a belief that markets are the most efficient means of the production and distribution of goods and services. They’re also the fruit of social prosperity and distribute wealth generated in the economy fairly and efficiently.

The organising principle — in theory, markets organise themselves through prices — and prices alone. Prices are determined in a decentralised way through the laws of supply and demand. If demand exceeds supply at a given price, prices increase, leading to decreasing demand. If supply exceeds demand, prices decrease, leading to increasing demand. Once supply equals demand, it results in market equilibrium and an optimal price.

The role of the private sector — taken to its extreme, a self-regulating market economy provides for every conceivable need and want. So essential services, like schools, health care, transportation, energy, and even prisons, are managed through competitive markets. The crucial factor when it comes to a self-regulating market system is that markets should not be influenced by any regulations from governments because regulations distort the smooth workings of the market system.

The role of government — the role of government is merely to protect the peace and defend property rights. Anything, and everything else, should be organised by the market.

What does this mean for taxes? They should be kept to an absolute minimum (or eliminated altogether) because the market system provides for every conceivable need.

The centre — mixed or balanced economy

The idea — the means of production is privately and publically owned.

The ‘mixed’ economy was the brainchild of the British economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynesian economics centred on ‘aggregate demand’. Keynes argued the total sum of spending by households, businesses, and the government was the most important driving force in an economy.

The organising principle — underlying a mixed economy is a balance between the public and private sectors. The mixed economy is underpinned by strong regulation of markets and a strong welfare state.

The role of the private sector — the private sector plays an important role in society, but crucially markets are regulated by the government to ensure they deliver positive social outcomes.

The role of government — the government has far more influence in society through ‘welfare states’. A welfare state centres on a belief that the government has a responsibility to end poverty by providing basic economic support for all members of society.

The public sector is far larger, with essential services like healthcare, education, energy and transportation being nationalised and managed by government departments.

What does this mean for taxes? The tax system is progressive, so the more you earn, the more you pay.

The left —a centralised economy

The idea—socialist economies are centrally planned, meaning the government owns the means of production.

The government controls every element of the production and distribution of goods and services. They also control how wealth is distributed throughout society.

The role of the private sector — in theory, there is no need for a private sector.

The role of government — the government is all-encompassing and controls every element of the economy. The government is the one and only employer and guarantees everyone a job.

What does this mean for taxes? The fact government provides for every conceivable good and service eliminates (or dramatically decreases) the need for taxes.

A sustainable future

In reality, the extremes of a self-regulating market economy on one hand and a centralised, controlled economy on the other, have never fully materialised. What has come to exist is different variations of the spectrum. Most governments pitch themselves somewhere near the middle. Governments that take more control of the economy are veering to the left. Governments providing more freedom to markets are veering to the right.

What’s clear is that each organising principle leads to dramatically different societies with very different social outcomes. And yet they all have a critical shared characteristic. Each system has a common goal — to achieve economic growth. How growth is achieved is the thing that separates them but it’s this shared goal that is so important when it comes to deciding which wing is best placed to move us to a sustainable society.

First of all, it’s important to reflect on why growth is the common goal. Before the Industrial Revolution, the vast majority of people lived in dire poverty. With industrialisation, the potential for sustained growth became a possibility for the first time. Growing economies help reduce poverty because growth leads to more wealth. More wealth leads to higher incomes. Higher incomes lead to increasing living standards. Increasing living standards lead to higher well-being.

It’s understandable then why economic growth has been so important and why it came to be a common goal. The thing is, none of these systems ever contemplated the possibility that one day we might just reach limits to growth.

That’s where we find ourselves today. The global economy has become breathtakingly efficient at producing goods and services. Those goods and services don’t appear out of thin air — they require massive amounts of energy and resources that are sourced from the natural world. A result of our ability to continually overproduce and overconsume (which is what leads to growth), the global economy has grown enormously in scale. To the point where we’ve exceeded the Earth’s carrying capacity. Carrying capacity is defined as the maximum “population size of a given species that an area can support without reducing its ability to support the same species in the future.”

In other words, our way of life exceeds the capacity of the Earth to continue to support our way of life. We now find ourselves in a state of ecological overshoot. Overshoot is why the climate is warming. It’s why biodiversity is collapsing. It’s why habitat is being destroyed. Whatever way you look at it economic growth can’t be sustained on a finite planet forever. And if it can’t be sustained then economic growth as the goal underlying all economic activity is unsustainable.

Economics for the twenty-first century

So which political system is best placed to lead us to a sustainable future?

Given growth is the goal of each system, the inconvenient reality is that none of these systems can move us to a sustainable future. What we need is a political system fit for the twenty-first century. One that reflects conditions as they are now, not as they were during the Industrial Revolution.

Post-industrial societies require post-growth economies. They need a new social goal — not one focused on being the richest but one focused on non-materialistic sources of meaning and satisfaction. They need to measure success differently, not just to assume that increasing GDP must be increasing well-being, but to measure whether people’s well-being is increasing.

A post-growth economy will represent a total departure from what we have. It will be marked by flavours of the current spectrum. There will still be markets and there will still be governments. But how these institutions come to be organised and the metrics they’re held against will be incomprehensibly different.