Having the right idea at the right time can be a game-changer

Early in 2000, Marc Randolph and Reed Hastings, the founders of Netflix, sat nervously in a meeting room at Blockbuster’s headquarters in Dallas, Texas. At the time, Netflix was a two-year-old startup lending DVDs to people through a website. They had 100 employees and 300,000 subscribers. In 1999, they had made a $57 million loss. In contrast, Blockbuster, worth $6 billion, was the dominant player in the home entertainment industry. It was a David meets Goliath kind of situation.

The two founders were awaiting John Antioco, the CEO of Blockbuster and a man renowned as a strategist. This gave Marc and Reed confidence in their proposal because they believed the Internet would transform the home entertainment industry beyond recognition. They pitched John an idea where Blockbuster would buy Netflix for $50 million, leaving Marc and Reed to develop and run blockbuster.com as the online video rental arm of the business. John scoffed at the value and refused to buy.

Fast forward twenty-four years and Netflix has over 238 million subscribers. The company has a market cap of $200 billion. Blockbuster, meanwhile, went bankrupt in 2010. The fancy headquarters in Dallas is long gone, all that’s left is one video store in Bend, Oregon.

In his book No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention, Reed poses the question, “How did this happen?” To which he responds:

“That day we went to Dallas, Blockbuster held all the aces. They had the brand, the power, the resources, and the vision. Blockbuster had us beat hands down. It was not obvious at the time, even to me, but we had one thing that Blockbuster did not: a culture that valued people over process, emphasised innovation over efficiency, and had very few controls…Netflix is different. We have a culture where No Rules Rules.”

At first glance, Reed’s explanation seems reasonable enough. But when you think about it, Netflix operates in a market (the home entertainment industry). That market is part of a web of thousands of markets that combine to form the global economy. In turn, the economy is the means through which we produce the goods and services needed to provide for the needs of society. When combined, they form a socio-economic system. Each system within that system conforms to a set of rules. Netflix is no different. They do conform to rules, the same rules every other company, institution and individual conforms to.

What the example of Netflix illustrates, though, is that within that dizzyingly complex construct that is the socio-economic system, transformation does take place. The home entertainment industry has transformed from people going to their local Blockbuster to rent videos and DVDs, to one where videos and DVDs no longer exist. Now, Netflix is a purely digital operation and has become embedded in your TV, where you can pick from thousands of different films or TV programmes.

So how did Netflix transform the market?

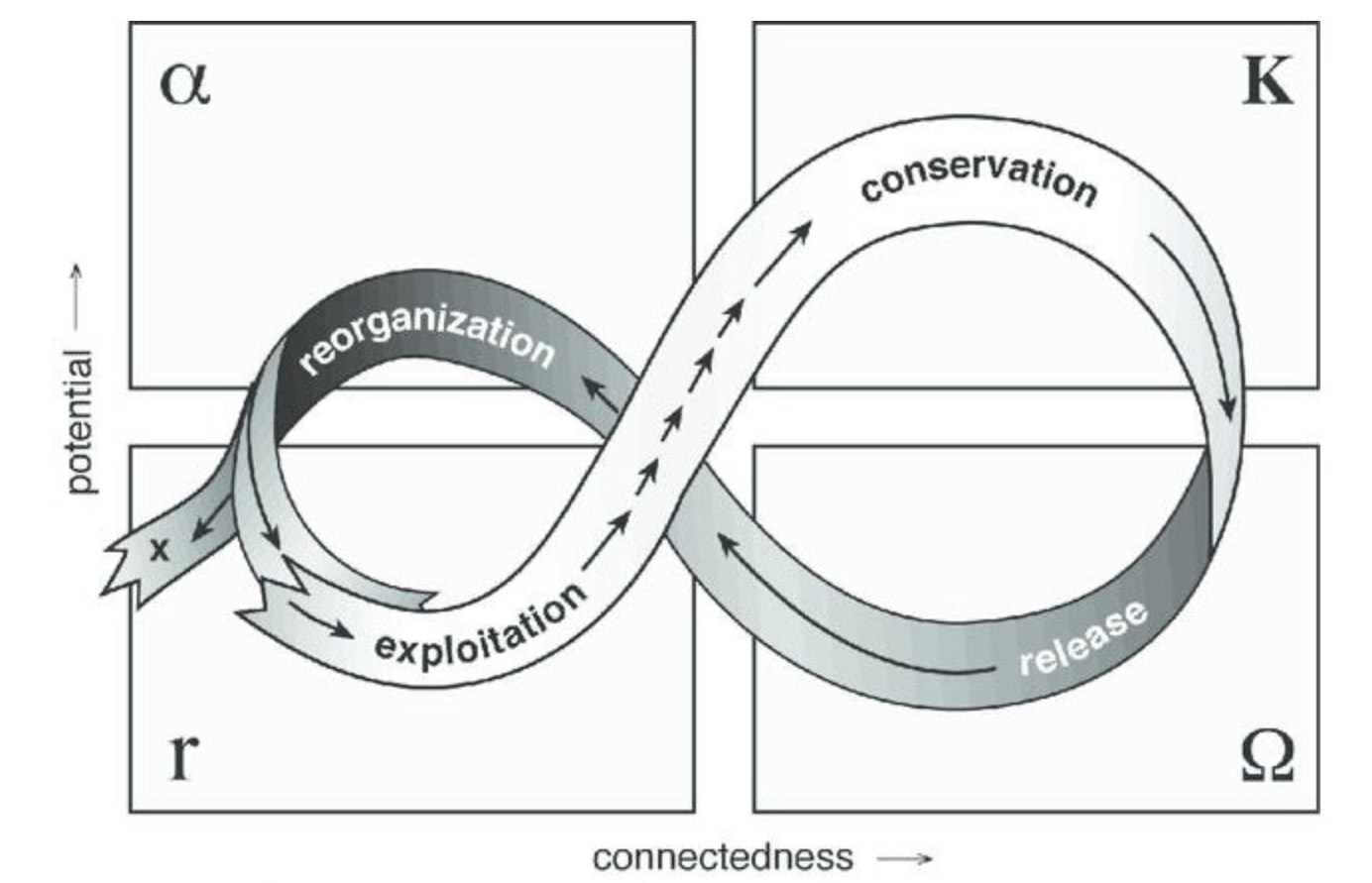

They just so happened to have just the right idea at just the right time. The adaptive cycle helps visualise why their idea was so transformative and how it is that they came to dominate the market. The adaptive cycle helps to visualise the process of change in complex systems like society and the economy. As the image shows, the adaptive cycle goes through four stages — Conservation, Release, Reorganization and Exploitation (or Innovation). We’ll use the rise of Netflix to help explain each phase of the cycle.

When Marc and Reed went to Blockbuster’s headquarters in 2000, the home entertainment industry was in the Conservation phase of the cycle. The Conservation phase is a market in equilibrium, (the majority of markets will be in this phase the majority of the time). In the Conservation phase, there is a subscribed way of doing things that creates resilience and stability within a market.

In the economy, this stage can also be referred to as the ‘monopoly’ phase because, in free markets, there is a tendency for large companies to kill off competitors, allowing them to dominate and control the market. Think Starbucks with coffee shops, Apple with smartphones, and Microsoft with computer software.

As the dominant player in the home entertainment industry, Blockbuster could crush competitors by lowering prices — making it difficult for competitors to establish themselves within the sector. Given the landscape Netflix was operating in, it’s understandable why Marc and Reed went to John Antioco with their proposal. Blockbuster had the means and resources to scale Netflix’s business model. But John saw a stable market with Blockbuster as the dominant player. You would imagine this is the reason he refused to pay $50 million for Netflix. He was so confident in his company’s ability to deal with the competition that he saw Netflix as irrelevant in the market his company dominated.

As Blockbuster was about to experience, markets are influenced by changes in the wider economy and society. However, it can be tricky to predict how changes or innovations will influence market dynamics because society and the economy are complex nonlinear systems.

Tim Berners-Lee’s invention of the internet in 1989 wasn’t just any old change, but it took time for the internet to begin reshaping how we do things. Even by 2000, the vast potential of the internet remained untapped. In hindsight, it feels obvious that a host of markets were moving inexorably towards digitalisation. Marc and Reed saw that untapped potential, but clearly, based on Blockbuster’s reaction to their proposal, it wasn’t apparent to everyone.

As the influence of the internet increased, the home entertainment market moved into a new phase — Release. The trigger point that shifts a market from Conservation to Release is known as creative destruction. How can destruction also be creative, you might ask? In Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, the economist Joseph Schumpeter argued that capitalism’s success is based on its ability to adapt to a changing environment. The development of new markets due, for example, to technological innovation, means capitalism is constantly evolving and mutating. An outcome is that change:

“incessantly revolutionises the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one. This process of creative destruction is an essential fact about capitalism. It is what capitalism consists in and what every capitalist concern has got to live in.”

He goes on to say;

“every piece of business strategy acquires its true significance only against the background of that process and within the situation created by it. It must be seen in its role in the perennial gale of creative destruction.”

Incessant change means the continued success of any business hinges on its ability to read those changes and respond to them accordingly. What makes capitalism such a successful economic system is that the process of change is spontaneous. No one manages this process, but the ever-evolving nature of markets means companies must also evolve to stay ahead of the game. Should a company rest on its laurels, fail to innovate or read changing market conditions, and it’s all too easy to be blown away by that perennial gale of destruction.

Once creative destruction is triggered, the cycle quickly moves from Release into the ‘Reorganisation’ phase. In an industry, the Reorganisation phase “is essentially equivalent to one of innovation and restructuring.” This phase is marked by unpredictability as the market is morphing into a new iteration. Netflix was in the perfect position to take advantage of this transformation as its business model complemented the reorganisation that shifted the market away from the store-based model towards digitalisation.

To his credit, John did react to the reorganisation of the market. In August 2004, Blockbuster, as John puts it, “jumped into the online business in a big way.” But the company’s leading shareholders disagreed with the direction John was taking the business so he was sacked and replaced with Jim Keyes in 2007. With his introduction, Blockbuster adopted a suicidal strategy:

“Keyes made it very public that management planned to drastically change the strategy. The company announced a big price increase for online customers, cut way back on marketing, and decided to intensify the focus on the store-based business.”

Blockbuster’s strategy was catastrophic. They failed to read the changes in the market that were making the store-based business model defunct. Rather than reorganising in line with those changes, they doubled down on a dying business model. Blockbuster was blown away by that perennial gale of destruction because they were too resistant to change. Goliath, in this case, was not killed by David. Goliath committed suicide due to its failure to adapt to a changing market, eventually leading to its bankruptcy.

As a market reorganises, it quickly flows into the ‘Exploitation’ or ‘Innovation’ phase. It’s here where Netflix’s culture played an essential part in its success. Employees not constrained by ‘rules’ could innovate in line with changes brought about by the reorganisation. In the innovation phase, entrepreneurs come into their element. They see opportunities (and are brave enough to pursue them) that few others can see.

It’s in the innovation phase where “startup organisations, whether in businesses, research, or policy, initiate intense activity energised by a pioneer spirit and opened opportunity.” At first, ideas abound. It feels like anything is possible because the constraints there once were, have gone. Lots of ideas won’t work. The ones that do mean certain companies or entrepreneurs begin establishing themselves in the market.

The Innovation phase can create opportunities for large profits, but those opportunities are quickly taken advantage of by those in a position to do so. Opportunities for innovation don’t last long because “markets start to become controlled by products once they exceed about 5 percent of the potential.” Once they do, the Innovation phase moves back towards equilibrium and into the Conservation phase of the cycle.

Today the home entertainment industry is in a similar position to the 1990s. Only now, rather than Blockbuster, Netflix has become a dominant player in a saturated market. As one of the industry’s leading figures, they can now crush the competition and make it difficult to enter the market. Those that have, such as Amazon and Apple, have unlimited resources and investment behind them to do so.

The adaptive cycle is a metaphor to help understand and interpret how social and economic systems change. The cycle demonstrates there are periods of stability and instability within markets, the economy and society generally. “All actors…can be present throughout — pioneers, consolidators, mavericks, revolutionaries, and leaders. It is their role and significance that change as their actions create the cycle.”

So entrepreneurs avoid markets in the Conservation phase because there is little potential for innovation. That doesn’t mean entrepreneurs don’t exist; it’s just that their influence in a market is less influential during the Conservation phase. These individuals are in their element in the Reorganisation and Innovation phases as they see opportunities to create new businesses based on a change that has created newfound opportunities.

This doesn’t make it any easier to foretell changes in markets. That’s why it’s so rare that a startup ends up rising to the top. Those that do share plenty of similarities to Netflix. They have the right idea at the right time, and crucially they have the right culture to innovate as a market is in a state of transformation.