And why chickens can’t lay square eggs

There once lived a chicken who had a peculiar dream. That dream was to lay a square-shaped egg. The chicken spent every moment of every day in pursuit of that dream. It changed its diet. It went on a rigorous exercise regime. It slept during the day and stayed awake at night. But no matter how hard it tried, those eggs remained stubbornly oval-shaped because the chicken couldn’t escape the limitations of the system defining its existence.

To lay a square-shaped egg the chicken would have to influence millions of years of evolution. The chicken was a victim of a catch-22. A catch-22 is defined as an impossible situation because you cannot do one thing until you do another thing, but you cannot do the second thing until you do the first thing.

Companies embracing sustainability are a bit like that chicken trying to lay a square-shaped egg. Just like the chicken, businesses operate within a system that is an outcome of an evolutionary process. Only this process is a social one. Take the economy — it’s not like the rules of the game that govern markets have appeared out of thin air. And neither have the businesses that comprise those markets.

Unlike the chicken that is unaware it’s a product of an evolutionary process, businesses can adapt how they produce goods and services. By embedding sustainable principles into business models, thousands of companies are producing goods and services that seek to minimise environmental costs, while maximising social value.

The desired outcome is to produce goods and services that people value, while detaching any environmental impacts from the production, transportation, sale and use of those products. They might do that by using recycled materials to create the product. By designing the product with circularity in mind. By producing products that are not designed for planned obsolescence (they’re not designed to break).

These companies are sustainability pioneers who have started to lay square-shaped eggs. By doing so they have triggered an adaptation in how businesses do business. This adaptation offers promise. As more consumers prioritise environmental considerations when choosing what to buy, and what not to buy, the idea is that we’ll eventually reach a point where the sustainability pioneers will be the leading players in markets.

Those who haven’t adapted will be forced to play catch up to remain competitive. Once sustainability becomes the new norm, we’ll reach a point where every company is laying square-shaped eggs. We’ll still produce the products and services people value but in radically different ways. Ways that dramatically decrease our environmental impact as a global society.

It’s for this reason that lots of politicians, economists and business people are optimistic that the innovative power of markets can trigger transformation from within.

With so many companies embracing sustainability, it does feel like we’re on the cusp of transformative economic change. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Sustainability pioneers may be producing products in different ways, but they remain victims of a catch-22.

The rules of the game

Just like our chicken, whether they like it or not, no business can escape the limitations of the capitalist system which defines its existence. So what are those limitations?

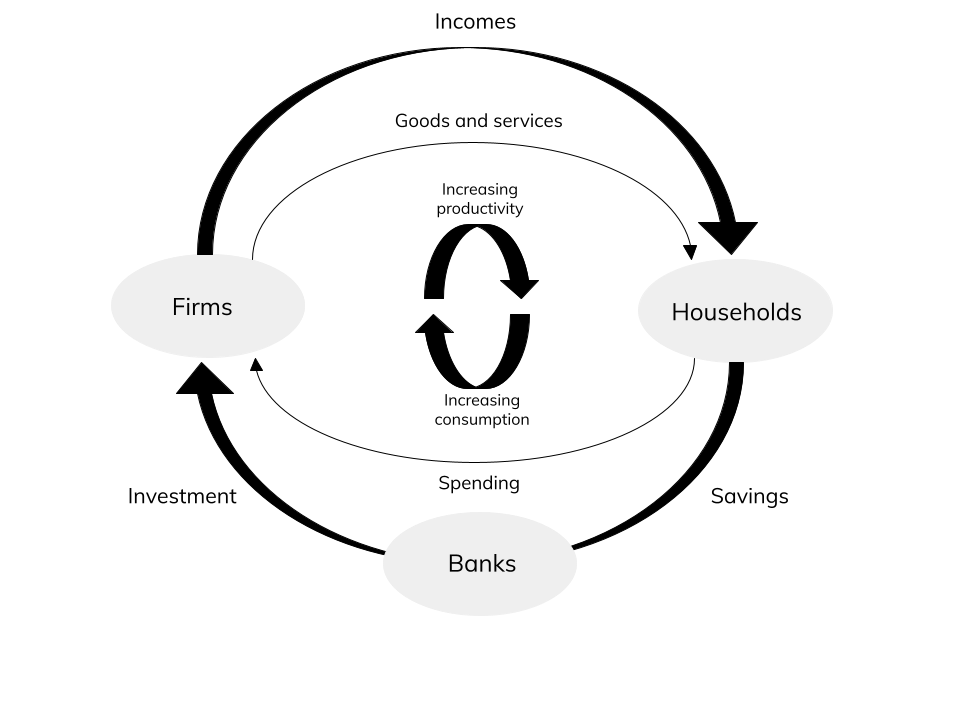

The circular flow of the economy visualises how capitalism works. There are three protagonists involved in the circular flow of the economy: firms, households (comprising people) and banks. Their roles are as follows:

- Firms — invest in capital, like buildings and machinery, to produce the goods and services households want and need. Firms employ people from the labour force to make goods and services. Revenue from the sale of goods and services allows firms to pay employees income.

- Households — offer their labour to firms in exchange for income. People spend some of their income on consumer goods, while saving the rest in banks.

- Banks — use some of the savings from households to invest in firms.

As we’ve said, sustainable pioneers differ from traditional businesses in how they produce goods and services. But when we look at the economy as a system, with sustainable firms embedded within a larger economy, that is the only way they differ from traditional companies.

Let’s take investment as an example. The sustainable pioneers can’t produce anything without capital. Companies raise capital through investments from banks or an investment fund. The company can then use that capital to make investments that allow it to produce the goods and services that make it a viable business.

Investors don’t give money away for free. A company will fail to raise capital if it can’t demonstrate how the investor will realise a return. By ‘demonstrating’, what we mean is, how can the business increase revenue year on year by selling more goods and services to households? This is a crucial consideration for investors because if the company can continually sell more, it increases revenue, which allows the company to grow. A growing company should eventually become a profitable one, which leads to handsome returns for investment funds, or in the case of banks, inspires confidence that the company will be able to pay back the loan at interest.

It’s a similar story for every other element of the model. Sustainable pioneers still hire employees from the labour force and they still pay them an income for their labour. Sustainable pioneers are still driven to increase productivity because that allows them to reduce costs, which allows them to increase revenue, which allows them to grow. Their relationship with households also remains the same — they need people to increase consumption because that allows every company to increase revenue.

No company can exist outside of this system, and a company that doesn’t exist is hardly sustainable. A company that is driven to become sustainable can only truly be sustainable if the economy it operates within is based on sustainable principles. The problem with capitalism is that it is unsustainable by design. That is why sustainable pioneers face a catch-22.

This catch-22 needs an explanation. First of all, why is capitalism unsustainable? Secondly, if companies can adapt business models, then why isn’t it possible for lots of companies to change the rules of the game governing the economy?

Existing in a void

When it comes to what makes capitalism unsustainable the circular flow of the economy omits a rather important protagonist, the environment. As the economist Herman Daly puts it in Beyond Growth, the circular flow of the economy is a “self-sustaining isolated system, a giant perpetual motion machine.” This abstraction means the circular flow of the economy ignores the idea of finitude or that we interact with, depend on, and impact the natural world around us.

To put it another way, the circular flow of the economy exists in a void. Seemingly the energy and resources used to make goods and services appear out of thin air. The same goes for any waste resulting from economic activity.

That’s fine though because it is only concerned with economic affairs, more specifically, it helps visualise the economy’s fundamental purpose — how economic growth is achieved. The thing about economic growth is that this isn’t just some desirable outcome. If GDP (how countries measure growth) doesn’t increase, it leads to a crisis. If GDP reduces it will lead to recession, if an economy continues contracting it will lead to depression, beyond that lies the spectre of economic collapse.

Capitalism depends on never-ending growth to sustain itself. There are two major reasons why growth as an economic objective is unsustainable.

First of all, a growing economy requires ever-increasing throughputs of energy and resources. This is problematic because, based on the laws of thermodynamics, infinite growth on a finite planet is impossible. Eventually, we’re going to run out of the throughputs that are required to make all of the stuff that makes economic growth possible.

The other side of the unsustainability of never-ending growth is that the economy has grown enormously in scale. The global economy is now so big that it requires more energy and resources than can be renewed by the Earth in a given year. This situation is known as ecological overshoot. When it comes to waste, overshoot translates into devastating environmental impacts, such as increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases that have led to a climate crisis.

Economic growth can’t be sustained if we want to maintain civilisation, but it’s the thing that must be maintained if we want to maintain the ‘health’ of the economy.

Resilience

Hang on though, if our sustainable pioneers are producing goods and services differently then isn’t it possible to transform the economy from within?

This is the issue with complex systems like nature and society. The structure of such systems makes them highly resilient to transformative change.

If you think about the world you were born into, yes, there have been cultural and technological changes, but by and large, the rules governing society remain the same throughout a lifetime. The stability created by this resilience is important because functioning societies could not be if the norms and rules governing each member of society changed from week to week, or year to year. Could you imagine how chaotic life would be if everyone was playing by different rules?

It’s economic considerations that bind modern society together. You can see this in your daily life. It’s simply not possible to be a functioning member of society if you don’t interact with the economy. It is, then, an all-consuming system.

What companies can and can’t do is constrained by what is possible within this economic structure. They may be able to lay square-shaped eggs, but they’re still required to lay eggs in the same way. What’s required to move to a sustainable society is a different type of farm and chickens operating in radically different ways.

Ironically, the development of capitalism suffered from a similar catch-22 as the sustainable pioneers. In eighteenth-century France, the bourgeoisie had taken the lead in finance, commerce, and industry but, as Jack Goldstone puts it in Revolution and Rebellion, “the growth of capitalism, which formed the basis of bourgeoisie power, was held in check by the feudal structure of society and by traditional systems of regulation affecting property rights, production and exchange.”

A feudal social structure wasn’t compatible with the development of a capitalist society, nor with the increasing influence of the bourgeoisie. It was the very thing that was holding back its development. The bourgeoisie were shackled by a feudal system defined by privileged orders. The only way they could escape its shackles was when the system broke down. Social breakdown broke the bonds that made society so resilient and sparked the French Revolution which ultimately led to the redesign of a society that was complementary to capitalist ideals.

The same obstacles apply now. Sustainable pioneers want to do things differently, what’s holding them back is a social structure that is incompatible with sustainable principles. In a similar way to pre-revolutionary France, the only way sustainable ideas can become the foundations of the economy is when society breaks down.

Social breakdown will create a vacuum, a moment in time, an opportunity to do things differently. Seeing as we’re hurtling towards weather extremes that are set to translate into wave after wave of economic crisis, it’s likely we are moving towards a situation where the conditions required for revolution become a distinct possibility. If that happens, our catch-22 will be no more. We’ll then be able to do the one thing that will allow us to do the other thing.